What Everyone Ought to Know About Iced Coffee & Cold Brew

Coffee on ice continues to be a growing trend in the US, and naturally factions have grown around the various favored brewing methods. We now have cold brew in abundance, canned coffee beverages, and copious ways to chill the hot stuff too. So, what's the consensus?

Three years ago, we first published our article exploring the differences between brewing methods for iced coffee. It’s since become one of our most popular and most commented-on blog posts, with some great insights by folks chiming in with their own experiments and findings. This year, cold coffee - and cold brew especially - continues to enjoy a growing and vocal fandom in the US. As more and more enthusiasts continue to explore cold coffee, we decided to revisit our previous article to adjust some techniques, add some new insights, and include a couple fresh recipes for you to try as well. Enjoy!

Iced Coffee Vs. Cold Brew

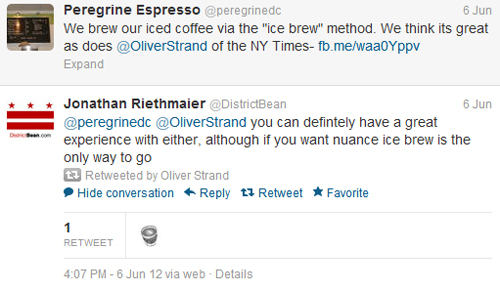

When we first launched this article, the coffee world was caught up in a Twitter-based tug-of-war about cold coffee in its various forms — and all of this before summer hit. It’s a polarizing topic that has invaded social media and intrigued coffee lovers around the world, and the momentum hasn’t yet died down.

Many are torn between methods, having known magical moments from both ice and cold brew, and we can’t help but agree. To navigate the discussion, we’ve explored the two main categories of iced coffee-making and asked what their loyal fans have to say in their defense. We won’t be lifting the arm of a single champion, but we’ll dance around the ring and let readers decide who deserves the belt.

Iced Coffee: Keep The Heat, Then Chill

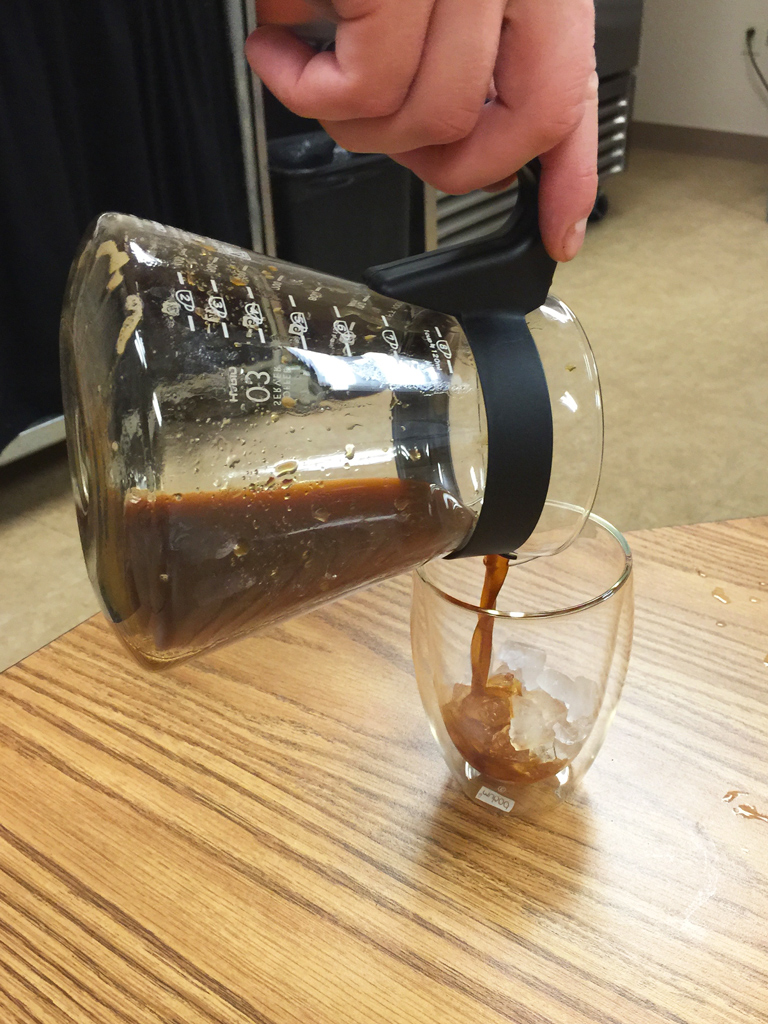

Affectionately referred to as the "Japanese iced method", ice brew is an intuitive option with a twist. It recruits classic devices like the Chemex, V60, or AeroPress and rearranges the recipes by adding ice early. When fresh coffee — brewed hot — lands on the ice drop by drop, it’s cooled instantly. The immediate result is chilled coffee that’s abundantly aromatic, agreeably acidic, and ready to drink.

This method answers some longstanding concerns about coffee served cold:

Iced coffee requires a ton of grounds, right? Not this coffee. Unlike other methods, the goal here isn’t to produce a concentrate that has to be cut with milk or water. While we recommend moderate updosing, there’s no need to use an exorbitant amount of beans. Cold, ready-to-drink coffee is a cinch without huge adjustments to ordinary ratios.

How can this coffee be anything but diluted? Again, it helps to use a little more grounds than usual. And by introducing hot coffee to ice drop by drop, the coffee cools faster and doesn’t melt as much ice. Contrast this with pouring an entire cup of hot coffee over ice at once: the ice melts quickly, along with the dreams of the poor sap who’s staring at a watery brew.

What about all that bitter, flavorless iced coffee that restaurant chains serve? This is the result of a devastating chemical phenomenon called oxidation, which takes place when coffee sits for a long time. And it elevates this conversation to the high realm of science. Lab coats on.

Unlike humans, coffee in both its roasted bean and brewed form dislikes oxygen — in fact, they’re sort of enemies. As it turns out, oxygen is a rather oppressive element and terrorizes the naturally occurring oils in coffee, making them taste unpleasant. The longer coffee is allowed to interact with this gaseous menace, the nastier it will become. Incidentally, oxidation is accelerated at higher temperatures, such as those at which coffee is brewed.

"It’s essential, then, that iced coffee, when brewed hot, is cooled as quickly as possible. Brewing directly over ice achieves this wonderfully."

But this chemistry lesson isn’t over just yet. In his endorsement of this brewing method, Peter Giuliano of Counter Culture Coffee and the SCAA Symposium, offers a few more helpful terms. The concepts of solubility and volatility will prove useful in this conversation.

Solubility describes the ability of a substance to dissolve in a solvent — or, in the world of brewing, coffee’s ability to dissolve in water. The changes we see (clear water becoming dark) are related to solubility. As was also true of oxidation, solubility is ramped up at higher temperatures, which is what leads to the generally accepted notion that coffee should be brewed with water between 195 and 205 degrees Fahrenheit. To brew at temperatures below this range, as Giuliano argues, is to leave desirable solids undissolved. (But more on that later.)

Another concept, volatility, describes the ability of a substance to vaporize — or, in the world of brewing, coffee’s ability to go airborne. The changes we smell (strong aromas filling the air) are related to volatility. Volatility also increases at high temperatures (see the pattern here?), so by brewing with hot water and cooling quickly the aromatics of coffee can be released and recaptured.

For obvious reasons, ice brew has caught some serious attention in the industry. It’s simple, familiar, and supported by both taste and theory, which is always a satisfying combination. George Howell has described it as “the only way to do it” (Strand, June 2011) and Jason Dominy praises it for retaining the taste of regularly brewed coffee, only cold. Trying it for the first time, Giuliano remarked, “the aromatics that I was used to smelling in hot coffee, I could taste in iced coffee.”

Iced Coffee Recipe

a la Prima

Convinced? The recipe below is one of our favorites, but there are also great guides available from Peter Giuliano, Terroir Coffee's George Howell, The New York Times' Oliver Strand, Batdorf & Bronson's Jason Dominy, and CoffeeGeek's Mark Prince.

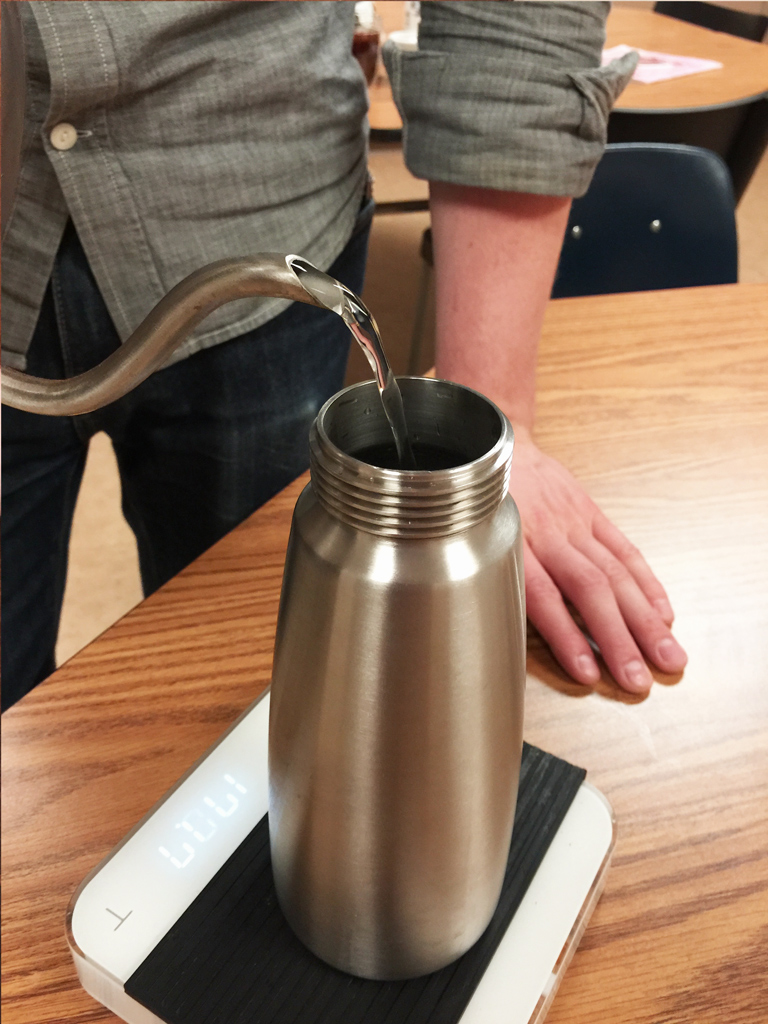

You’ll need your favorite pour-over device with a filter; 60 grams of coffee, ground medium; 500 grams of hot water; 200 grams of ice; a pouring kettle; and a cup or carafe.

- Assemble pour-over apparatus as per usual.

- Rinse Filter.

- Add ice to receiving vessel. Large cubes are preferable to small chunks.

- Pour water, heated to 195-205°F, into coffee using pouring patterns and practices appropriate to filter cone type. (Bonus points for spelling your name.)

- Five hundred grams and 3:00-3:30 later, serve coffee in a glass of ice.

Crash-cooling: No Dilution, No Problem

The “Japanese” method works a dream with most coffees, but what if we could achieve the same effect without worrying about brewing at a higher strength to balance out the dilution? The answer is obvious and simple, but the execution is often rather kludgy.

To crash-cool, just brew your coffee as you normally would into a vessel with good heat conduction properties, like a stainless steel cocktail shaker or large steaming pitcher, and then stick it somewhere cold. The freezer will do the job if it must, but it will take about an hour to cool down your brew - not good if you’re in a hurry, and certainly not good if you’d prefer to avoid oxidation. Instead, we recommend placing your cocktail shaker (a tall, thinner vessel introduces more surface area for cooling) into a container full of pulverized ice, add just enough water to cover the ice, and gently stir your coffee. In just a minute or two, you’ll have delicious and refreshing crash-cooled coffee, ready to enjoy.

We do suggest brewing at a touch higher strength than normal, because as liquids get colder we tend to lose some of our sensitivity to their complex tastes. The volatility of cold liquids drops slightly as well, meaning the delightful aromas we appreciate in hot coffee aren’t quite as present when cold. Bumping up the strength just slightly helps to compensate for this, and makes for a tastier, sweeter beverage.

Another option soon to hit the market is a device called the Coil (the Coil is no longer available, check out the Hyperchiller) which is made specifically to crash-cool your coffee without dilution. Utilizing a stainless steel coil surrounded by ice water, your brews shed their heat as they flow downward into the carafe below. Those of you who brew your own beer will recognize the design - it’s almost exactly a wort chiller, miniaturized and styled for by-the-cup use.

The release of the Coil makes for one of the first dedicated coffee crash-cooling products on the market, surely with more to follow. While crash-cooling isn’t very common just yet, it’s easy to see why it’s a desirable cooling method for coffee, and we wouldn’t be surprised to see it making waves in the next few years as well.

Cold Brew: Cool From The Start, Worth The Wait

Famed for dropping jaws and teasing appetites, this is the legendary method that boasts a brew time between 2 and 24 hours — and sometimes longer. It’s theatrical and nearly ostentatious, but deceptively simple, and can be enjoyed with or without fancy equipment. Coffee is extracted with cool water, introduced either by full, immediate immersion or a slow, steady drip. Should one survive the wait, they’ll enjoy a sweet, syrupy cup that sidesteps coffee’s normal acidity and goes down smooth.

Cold brew has its own posse of proponents, who love that it’s solved some of their dilemmas:

Coffee with cream is a classic, but something seems off when the "Japanese iced method" meets milk. What’s going on here? It’s a matter of personal preference, but whoever asks this question is on to something. Strand suggests that "cold brew complements the rich sweetness of dairy", while ice brew is just meant to be enjoyed au naturel (Strand, June 2012).

Offering ice brew by-the-cup asks a lot of an already-busy cafe, but customers love their coffee cold. Is there anything more efficient out there? Yes — and it doesn’t involve using the rancid leftovers from the last bulk batch. Cold brew only requires a little human involvement at the start and finish, and in between replaces the busy barista with the gentle prowess of time. Strategically scheduled brews can allow a cafe to supply a steady stream of chilled coffee without demanding the constant attention of its staff.

Does brewing with cold water line up with that earlier chemistry lesson? Positioning science over the senses is a dangerous move when it comes to coffee — tastebuds, not textbooks, should make these decisions — but it does help to let research inform the discussion. Lab coats again, please.

Defending cold brew, Lorenzo Perkins of Cuvee Coffee refers to an intriguing trend described in The Coffee Brewing Handbook by Ted Lingle: apparently the presence of generally unfavorable compounds (infamous for their long names) decreases at lower brewing temperatures. As Nick Cho (Wrecking Ball Coffee Roasters) points out, these results were seen at temperatures around 158°F, which isn’t exactly “cold”, but there seems to be a pattern here (Cho, May 2012). Perkins suggests that cold brew’s unique sweetness has something to do with the fact that nasty compounds shy away from cold water.

"Positioning science over the senses is a dangerous move when it comes to coffee — tastebuds, not textbooks, should make these decisions..."

As sweet as cold brew can be, coffee does have some positive compounds that are rather particular about being extracted only by hot water. Perkins’ quick fix: start hot, finish cold. His method splits the total water volume 80/20, reserving the smaller share for hot water and then continuing with cold brew as normal. By his estimation, this should extract all desirable solubles — those both deep and delicate — and minimize the presence of those less welcomed.

However, oxygen is impartial in its treatment of coffee and quickly trashes ice brews and cold brews alike. What, then, can be done about a method that requires several hours to sit and steep? Minimizing the coffee’s exposure to oxygen is a must, and can be achieved simply by using a container that holds only the desired volume of coffee and water and no more. For extra security the entire apparatus can be stored in an anaerobic environment. Dwelltime in Cambridge, Massachusetts is among the first to keep cold-brewed batches in a nitrogen-fed kegerator, a technique that Perkins also recommends.

But Dwelltime isn’t alone on the cold brew side — not even close. It’s gone from obscurity to all-star status in a few short years, and it’s still climbing the charts. Jay Caragay employs cold brew towers at his Baltimore cafe, Spro Coffee, and loves that his customers enjoy the visual excitement. (Uniquely, Caragay matches coffees to brew methods, so there is no monopoly of method at Spro.) Orange County’s Portola Coffee Lab also makes use of both ice and cold brew methods, but enjoys their Kyoto-style dripper for its distinct sweetness and the complexity that comes with constantly moving water.

Cold Brew Recipe

a la Prima

Care to give it a try? The recipe below is one of our favorites, but there are also great guides available from Cuvee Coffee’s Lorenzo Perkins, Barismo's Jaime van Schyndel, and Square Mile’s James Hoffmann.

You’ll need an AeroPress with 2 filters (at least one should be paper); 45 grams of coffee, ground medium-fine; 300 grams of water; 200 grams of ice; a water bottle (Dasani works well); a sewing needle, a sharp blade, and a mason jar.

- Empty water bottle and cut off bottom with sharp blade.

- Remove bottle’s cap and puncture with sewing needle, creating the smallest hole possible.

- Replace cap and test flow by filling with water and watching drip rate, aiming for about 40 drops per minute. Alter hole size as necessary.

- Rinse filter and assemble AeroPress, filling with coffee.

- Moisten grounds with

warmcool water and mix gently, subtracting water used from total water volume. - Level coffee bed with finger.

- Trim paper filter to fit inside of AeroPress tube and place atop coffee bed, pressing softly to level.

- Place Aeropress on jar and mount bottle on top.

- Fill bottle with remaining water and ice.

- When bottle is empty, disassemble and enjoy.

Hot Bloom Cold Brew Recipe

a la Prima

Proponents of cold brew love its milder acidity and round sweetness, but sometimes that doesn’t quite do a particular coffee justice. A fresh crop Ethiopian or Kenyan can have a tantalizing acidity, which is heavily diminished when brewed cold. Thankfully, there’s an easy solution to get the best of both worlds - the sparkling zing of acidity with the sweet mellowness of cold extractions. All you have to do is introduce some hot water to the mix.

The “hot bloom” approach to cold brew allows more acidity to be extracted before a long cold steep, and it doesn’t require much modification to your normal cold brew recipe. Acids in coffee extract early and easily, but they are tempered greatly if the water is room temperature or colder. By starting hot, we can get just enough acidity to make those flavors pop, then we add cool water to slow the extraction down again to finish nice and slow

For this recipe, you’ll need a french press or a cold brewer like the Hario Mizudashi; 90 grams of coffee ground coarse; 200 grams of 200 F water; 500 grams of room temperature water; and 50 grams of ice.

- Grind coffee and add to your brewing device.

- Pour 200 grams of hot water over the grounds, saturating as evenly as possible. Stir the grounds to help saturate if necessary.

- Wait 60 seconds to allow the ground coffee to bloom.

- Add the remaining water and ice, and lightly stir the grounds to help them saturate. If using a Mizudashi brewer, pour the water slowly over the grounds in the filter basket.

- Place the brewer in your refrigerator, covered, and allow to steep for 12 hours.

- Strain and decant your cold brew into an airtight container, and cut with water to your desired strength. We like to add about 200 grams of water in most cases.

- Serve over ice, add a splash of cream, and enjoy!

Under Pressure: A Modernist Method

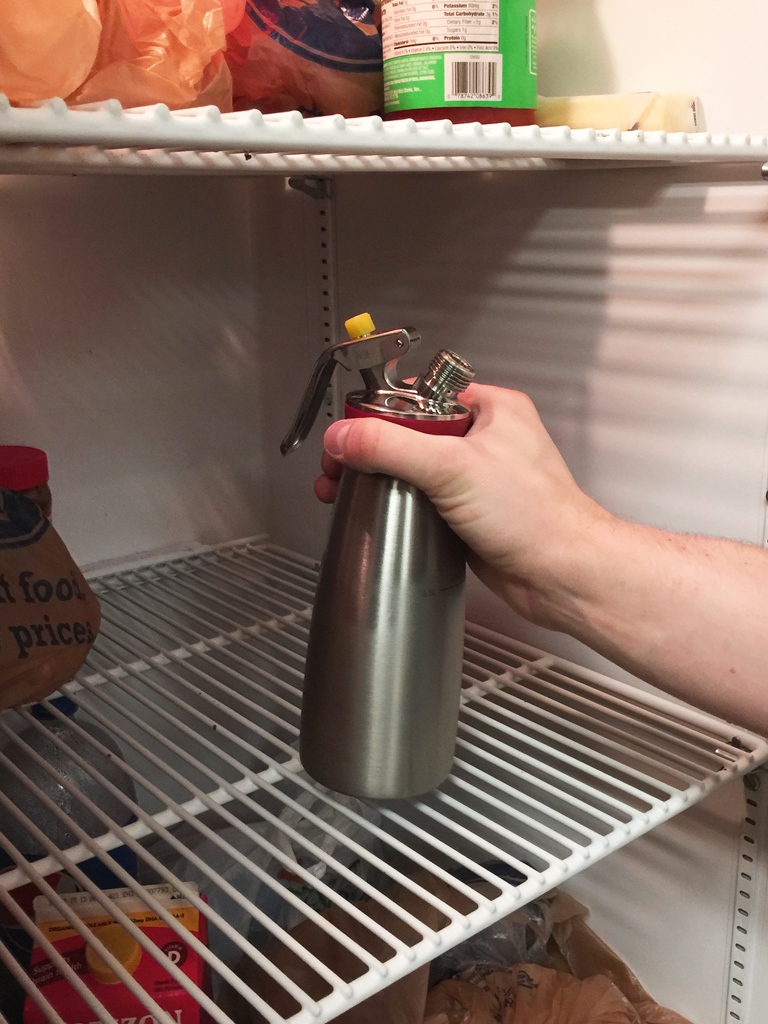

Cold brew is a dead simple and tasty way to brew coffee, but what if you could have similar results in a fraction of the time? Enter the whipping siphon, a tool which is no stranger to coffee shops, but isn’t often seen as a brewing device. The beauty of the whipping siphon is the ease of being able to pressurize liquids inside using inexpensive and inert nitrous oxide gas.

Nitrous oxide is essentially flavorless, it doesn’t readily dissolve into coffee, and it won’t react with your brew either. What it will do is pressurize the siphon chamber while your coffee steeps - but the trick is actually what comes later. When you depressurize the chamber, it causes cavitation in the coffee grounds. Gases inside the coffee swell and escape, allowing water to rush in and dissolve all the tasty goodness inside. Think of this as an extra bump in your extraction that rapidly brings your brew from weak to delicious in no time at all. To use an appropriate analogy, think of this as the same sort of boost you would get by adding a burst of nitrous oxide to your car’s engine. You may not win any drag races with your N2O, but you’ll still be sipping on some awesome coffee on the sidelines. You can even add other foods and spices to infuse into your coffee and take it to the next level, perfect for a specialty beverage or an addition to a coffee cocktail.

Pressurized Cold Brew Recipes

Want to give the whipping siphon a shot? Here are two recipes we enjoy; one created by the food geeks at ChefSteps, and one we designed in-house that’s even faster.

a la ChefSteps

You’ll need a whipping siphon (ours is a 1 US pint model made by iSi) with 2 nitrous oxide chargers (we also use iSi chargers); 60 grams of coffee at a medium grind; 300 grams of water. This is a very high ratio brew (1:5), so it’s meant to create a concentrate to be diluted with water when serving. You’ll also need a strainer or filter, and a Chemex or V60 will serve you well!

- Grind your coffee and add it to the siphon chamber.

- Add 300 grams of water, then screw on the siphon lid.

- Charge siphon with two chargers of N2O.

- Gently swirl the siphon to mix the coffee and water. Do not shake or turn the siphon over, as coffee grounds may become lodged in the valves.

- Place siphon in the refrigerator for two hours to brew.

- After two hours, remove the siphon and discharge the gas. Again, do not invert the siphon, discharge it while upright.

- Unscrew the siphon lid and pour the contents through a strainer or coffee filter.

- Dilute to taste and serve as desired. We like it plain, but a bit of cream is great too!

- Store in an airtight container in the fridge and consume within 3-5 days.

a la Prima

Our recipe is tweaked to get an even faster brew, and combines some of the other methods above for an end product that is crisp, cool, refreshing, and sweet. We’ll be hot-blooming our coffee before crash-cooling in the fridge, under pressure, and our brew will be ready in just 45 minutes.

You’ll need a whipping siphon (ours is a 1 US pint model made by iSi) with 2 nitrous oxide chargers (we also use iSi chargers); 30 grams of coffee at a medium grind; 150 grams of hot water at 190-210 F, and 150 grams of room temperature water. You will also need a tall container for an ice bath. We prefer crushed ice, but normal cubes will be fine. The container needs to be tall and wide enough for you to place your siphon into it, pack ice around it, then add some water to create an ice slurry for crash-cooling the coffee. As above, you’ll also need a strainer or filter, so prep that V60 while you steep. Our ratio is higher than normal drip coffee at 1:10, but it’s meant to be enjoyed straight and without dilution.

- Grind your coffee and add it to the siphon chamber. We also recommend sifting out your fines if possible, as they can lead to some overextraction in this method. A kitchen sieve should be more than enough, just sift your grinds for 30-60 seconds, and discard the fines. You may lose 5-10 grams of mass when sifting, so grind a bit more than you need.

- Add 150 grams of hot water, then swirl or stir to combine with the coffee grounds. Steep for 45 seconds.

- Add the remaining 150 grams of cool water, then screw on the siphon lid.

- Charge with 2 nitrous oxide chargers.

- Add the entire siphon, upright, to the tall container, then fill in the remaining space with ice.

- Add just enough water to the container to meet the fill line on the side of the siphon. Don’t overflow the container with water, you only need enough to create an icy slurry around most of the siphon chamber.

- Place entire container in the refrigerator for 45 minutes to steep.

- After 45 minutes, remove the siphon and discharge the gas. Again, always do this upright to prevent grounds from getting stuck in the valves.

- Unscrew the lid and strain the coffee.

- Serve straight or on ice. If you’re feeling really fancy, try garnishing with a carbonated orange slice!

Choose Your Brew

Fierce loyalties aside, all iced coffee fanatics approach their favorite recipes the same way: we tinker and taste, mull and measure until conjuring that one magical brew, for which all vitality has been exhausted. (Thankfully, that’s when the caffeine kicks in.) We’re known for our fascination with detail and our obsession with precise methods and predictable results. And, to us, preparing coffee is no less of a craft when it’s served cold.

With taste as a trusty guide and the technical stuff for tips along the way, we believe that your favorite cup of iced coffee isn’t far off. Just like your hot brew, it can be fresh and flavorful, bright and bursting with the exotic characteristics of its origin. If you try one of the recipes we’ve recommended, or discover something special of your own, share it on Twitter by mentioning @primacoffee. You can also leave your thoughts in the comment section below.

Here’s to keeping cool and caffeinated this summer.